MacMillan's 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach:

A Comprehensive Framework

to support neurodivergents and their families throughout adulthood.

R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse Programs For Professionals

WHAT ARE THE R.E.A.L. PROGRAMS?

Autism and other forms of neurodivergence shape how adults engage in social relationships—especially in families and intimate partnerships, where emotional demands run high and communication styles often differ.

Developed by Anne MacMillan, MLA, the R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse programs offer a clear, research-informed path forward. Built around a structured 10-step approach, these programs translate neuroscience, developmental psychology, and clinical insight into practical tools for real-life change. Adults gain access to targeted education, specialized assessments, and concrete strategies for building skills, making decisions, and strengthening relationships.

As awareness of adult neurodivergence expands, so does the demand for services that meet the moment—with depth, precision, and respect for every individual’s way of being.

WHY SHOULD YOUR PRACTICE USE THE R.E.A.L. PROGRAMS?

Neurodiverse families are commonly made up of autistic, attention neurodivergent (ADHD), and other neurodivergent family members. The different brains' different ways of perceiving and navigating the social world affect family social interactions, eliciting difficulties and distress that commonly lead to trauma and isolation.

In the mid-20th century, before neurodivergence in aNeurodiverse families often include autistic, attention neurodivergent (ADHD), and other neurodivergent members. Differences in how each brain processes social and emotional information shape everyday interactions—frequently leading to misunderstanding, relational strain, and social isolation.

In the mid-20th century, long before adult neurodivergence was recognized, psychology framed mental and relational challenges as evidence of disorder. Many neurodivergent individuals—unaware of their neurological differences—were mischaracterized as broken or dysfunctional. These labels disempowered them, and treatments that failed to account for brain-based variation often offered little meaningful support.

In the early 21st century, autism’s prevalence in children came into focus. Only now are we beginning to recognize the widespread presence of neurodivergence in adults. These adults are not disordered. They do not need to be “fixed.” They need access to insight, language, and tools that respect their neurology—so they can build skills, reduce suffering, and strengthen their relationships.

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse programs offer that path forward.dults was understood or recognized, psychologists began defining mental disorders that required treatment. Many neurodivergents, completely unaware that their brains were different, were unjustly labeled as "disordered" or "broken." These labels disempowered neurodivergents and treatments that didn't recognize brain differences offered little relevant support.

The high prevalence of autism in children was discovered in the early years of the 21st century. Today, we are finally recognizing multiple neurodivergencies in adulthood. These adults aren't "broken." They don't need "treatment" for "disorders." They need to understand the nuances of brain differences and have access to resources that will help them leverage their strengths and build skills to address their challenges.

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse programs offer solutions: solutions that work.

R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse

Resources & Education Across the Lifespan

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Author of the 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach, Speaker, Researcher, Consultant, Coach, Educator and Expert Witness

WHO ARE THE R.E.A.L. PROGRAMS FOR?

Our comprehensive 10-step method is designed for use by psychologists, therapists, social workers, counselors, teachers, coaches, consultants, clergy, domestic violence workers, victim advocates and more.

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach is a comprehensive 10-step method for coaches, consultants, teachers, therapists, psychologists, social workers, mediators, domestic violence workers, victim advocates, spiritual leaders, and more.

The approach is designed to support professional growth through both structured education and direct relational experience. To access the full programs, at least one provider per office must complete our NFS-E Credential and become a Neurodiverse Family Systems – Educator. This ensures that each office has a designated provider who understands the framework and can guide implementation with fidelity.

While only one team member is required to complete the full credentialing process, all other providers receive meaningful and accessible support to ensure high-quality care across the team. Every provider begins with a clear, neurologically informed orientation that introduces the program’s foundational concepts, implementation principles, and ethical guidelines. From there, learning continues through guided use of the program materials with clients. As clients move through the 10-step structure, providers gain access to corresponding provider resources—learning in real time how to support neurologically diverse adults with clarity and care.

This approach reflects a core truth of neurodiverse relational systems work: while structured training is essential, deep understanding develops through direct experience. The program honors this by allowing providers to grow alongside their clients. Even those who are new to neurodiverse systems will find that the materials are intuitive, grounded, and developmentally attuned—inviting providers to apply their own wisdom while building confidence in a new and important domain.

WHAT MAKES R.E.A.L. DIFFERENT?

Traditional interventions are grounded in the assumption that relationship conflict can be resolved through shared dialogue and emotional processing. But in neurodiverse families and intimate life partnerships, these methods often overlook the root cause of distress: neurological mismatch.

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse model introduces a fundamental paradigm shift. Instead of beginning with group sessions, we start with the individual—recognizing that perception, empathy, expression, and regulation differ profoundly across neurotypes. Our structured 10-step program replaces generalized talk therapy with neurotype-specific education, tools, and developmental supports.

This shift moves providers away from pathologizing behavior and toward honoring difference. It reframes family and intimate partnership conflict not as dysfunction, but as the result of unmet neurological needs—and offers a clear, compassionate pathway for lasting change, even when only one partner or family member is ready to begin.

HOW DO THE R.E.A.L. PROGRAMS WORK?

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach guides adults—and the professionals who support them—through a structured but flexible 10-step process designed to build insight, reduce distress, and support sustainable relational growth. Clients receive materials tailored to their neurology (autistic or non-autistic), while providers use parallel resources that align with the client’s processing style.

Each of the 10 steps addresses a core dimension of neurodiverse relational life—such as empathy differences, neurological mismatch, relational role entrenchment, boundary development, problem solving, and cycles of trauma. Steps are sequential but adaptable, allowing providers to meet clients where they are without sacrificing developmental integrity.

Clients move through video-based educational content, guided assessments, structured reflection prompts, and integrative exercises that help them make sense of their experiences through a neurologically attuned lens. Providers receive step-specific guides that support interpretation, discussion, and skill-building, ensuring that support remains aligned with the client’s neurotype and developmental readiness.

Unlike many traditional models that prioritize behavior change or surface-level communication strategies, the R.E.A.L. Approach integrates neurological, emotional, somatic, and systemic layers of experience.

Tools range from conceptual mappings and guided journaling to artwork-based exercises and somatic strategies—supporting a wide range of processing styles and learning needs.

Because each client engages individually, the program remains effective whether or not other family members or partners are involved. When multiple participants are ready, shared theory and neurologically specific tools create a common language for growth without forcing consensus or conformity.

About Anne MacMillan:

I built my original Neurodiverse Family Systems Theory on my education, personal life experience, and the professional experience I gained in the private neurodiverse services practice I founded in 2017.

Today, my services extend to support other professionals who have come to the new realization that neurodiversity is at the heart of many of the relationship challenges their adult clients face. Professionals can use my practical 10-Step educational system, including quantitative assessments, integration practices, and support resources to help their clients comprehend their relationship challenges and find the happiness and peace they deserve.

I have a research-based master's in psychology from Harvard University and studied developmental psychology as an undergrad. I received the Director's Thesis Award at Harvard for my original research on Level 1 autism and intimate life partnerships — some of the first quantitative research on the subject in the world.

Altogether, I have over 50 years of personal life experience with neurodiverse family systems (I was born into a neurodiverse family), over 20 years of personal life experience with neurodiverse intimate life partnerships, and 8 years of professional experience working with individuals managing the challenges of neurodiverse family systems.

I self-identify as a high body empathetic neurodivergent and attention neurodivergent (ADHD). I am not autistic.

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Author of the R.E.A.L. 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach, Speaker, Researcher, Consultant, Coach, Educator and Expert Witness

Recent Blog Posts

Anne MacMillan's 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach: A Framework for Supporting Level 1 Autistic Adults and their Neurodivergent and Neurotypical Family Members

Anne MacMillan's R.E.A.L. 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach supports Level 1 autistic adults and their neurodivergent and neurotypical family members as they seek to comprehend the conflict they are experiencing in their interpersonal relationships and then work towards practical solutions that will improve their quality of life. Her approach is sequential and structured yet offers the flexibility required when working with a wide spectrum of neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals having many different unique strengths and challenges.

Step 1: Accept Wholeness and Maintain a Future Orientation

MacMillan begins with a commitment to viewing both yourself and your family members as whole, capable individuals. This step emphasizes the importance of maintaining a forward-looking perspective, focusing on skill-building and actionable steps that pave the way for positive change.

Step 2: Identify and Comprehend Your Own Neurology

Comprehending one's own neurology and its associated strengths and challenges lays a foundation for understanding the self, one's own perception of the world, as well as one's own actions and experiences within a neurodiverse family system. Individuals are encouraged prioritize understanding their own neurology over their family members' neurologies and to respect and appreciate the self and one's own neurologically-based subjective experiences.

Step 3: Identify and Comprehend Your Family Members' Neurologies

The differences between Level 1 autism, attention neurodivergence (ADHD), high body empathy neurodivergence and neurotypical neurologies are not simple. Through understanding specifically how one's own neurology differs from one's family members' neurologies and what it means when one individual is of more than one neurology (e.g. autistic and attention neurodivergent), individuals can better understand their own experiences and the experiences and perspectives of their loved ones. This increased insight acts as a foundation for finding solutions, taking action and making positive change to improve relationships and quality of life. This step fosters mutual understanding and helps in recognizing the different ways each family member perceives and interacts with the social world.

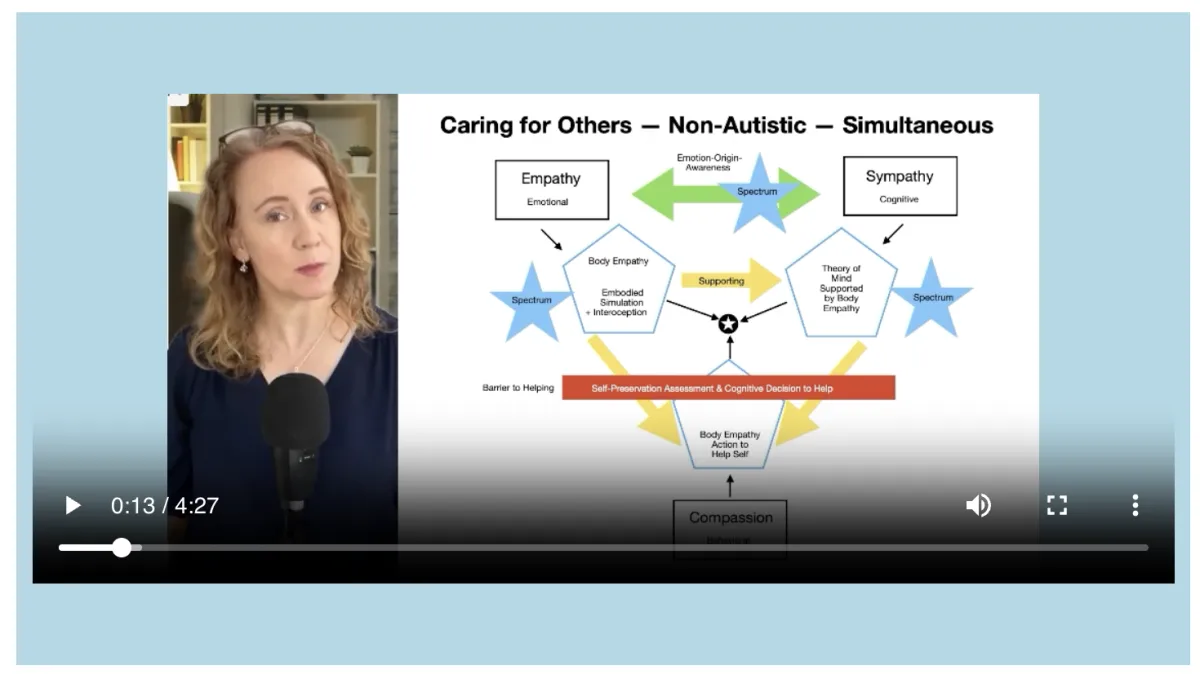

Step 4: Understand Empathy Differences

MacMillan defines non-autistic body empathy and autistic emotion-sharing empathy as well as 5 distinct empathy spectrums that all individuals, regardless of neurology fall onto: 1) the empathic-emotion intensity spectrum, 2) the emotion-origin awareness spectrum, 3) the embodied simulation spectrum, 4) the interoception spectrum, and 5) the theory of mind spectrum (MacMillan, 2025). She offers quantitative assessments to support individuals as they understand where they and their loved ones fit on these five spectrums (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 5: Accept That Both Autistics and Non-Autistics Can Engage in Harmful Narcissistic Behaviors

This step challenges individuals to recognize that both non-autistics and autistics are capable of engaging in narcissistic behaviors that harm their loved ones. The notion that all individuals of any particular neurology are generally innocent or harmless only prevents individuals and families from addressing the reality that, in many cases, they are experiencing narcissistic behaviors within their neurodiverse family systems. Individuals are asked to acknowledge that excusing adult narcissistic behaviors due to individual neurology does not help families move to healthier interaction styles.

The importance of understanding psychology in terms of spectrums or dimensions rather than "types" is addressed (Coolidge and Segal, 1998; M-A. Crocq, 2013) and the history of "Narcissistic Personality Disorder" and its associated and outdated subclinical types (grandiose and vulnerable) is investigated (Miller et. al, 2017). The association between Level 1 autistic adults and all the personality disorders and, specifically, the subclinical type of vulnerable narcissism (Broglia et al., 2023) are acknowledged and addressed, even as individuals are simultaneously encouraged to discard the use of personality types and all "disorders" when working with neurodiversity.

As it is common for autistics and non-autistics to perceive the world so differently that they are unable to agree on the root cause of much of their conflict, individuals are encouraged to evaluate observable behaviors rather than incentives are cognitive mechanisms and to decide if the behaviors are narcissistic or not. Alongside a quantitive narcissistic behavior assessment, a quantitative self-respect assessment is offered to support individuals in coming to an awareness of whether or not they have a tendency to allow members of their families to behave narcissistically towards them.

Abuse should not be tolerated regardless of the neurology of the abuser and the reality that both autistics and non-autistics can be offenders or victims is acknowledged.

Step 6: Learn About Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD)

Neurodiverse relationships have distinct dynamics that differ from neurotypical relationships. MacMillan defines Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD) as including differences in psychological functioning, difficulties with relationship functioning within distinct and specific social situations that affect relationship dynamics differently (MacMillan 2025).

Psychological functioning differences include attachment differences, boundary differences, identity formation differences, and intimacy differences (MacMillan, 2025).

Relationship functioning difficulties addressed included problem solving difficulties, action impact understanding differences, and difficulties associated with passiveness, assertiveness and aggression (MacMillan, 2025).

The varying impact of neurodiversity on different social situations is addressed. Adult friendships are distinguished from family relationships, and parent-child relationships are distinguished from intimate life partnerships. The impact of autism on flirting and courtship as well as sex is acknowledged and addressed (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 7: Comprehend the Role That Trauma Plays in Your Life

Multigenerational trauma and regular intermittent trauma spikes play a significant role in most neurodiverse family systems. Residual trauma can build up in the nervous system causing difficulties over time (MacMillan, 2025). Autistics may have more difficulties recovering from trauma than non-autistics (Peterson et al., 2019). Interoceptive abilities can aid trauma relief (Brewer et al., 2016; Reinhardt et al., 2020) and the fact that many autistics likely have lower levels of interoceptive perception than autistics means that autistics require different trauma support than non-autistics (MacMillan, 2025).

A specific form of long term low grade trauma experienced experienced only by non-autistics called body empathy non-reciprocation trauma (MacMillan, 2025) is defined and addressed.

Several quantitative trauma scales are offered to support professionals and clients in better comprehending the role trauma plays in individuals' lives.

Step 8: Identify and Comprehend Individuals’ Roles and Functions in Your Neurodiverse Family System

It is common for individual members of neurodiverse family systems to take upon roles that play both individual and systemic functions within their family system. These roles tend to be more intractable than roles in neurotypical family systems because they are facilitated by the family members' neurologies. Over 15 common roles are named and defined and individuals are offered resources to support them in coming to greater awareness of the individual and systemic functions the roles are playing in their neurodiverse family systems so that they can make actionable decisions with more self-awareness and awareness of their family systems (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 9: Identify and Comprehend Interaction Cycles and Their Associated Intermittent Trauma Spikes

Individuals in neurodiverse family systems tend to cycle through periods of relative calm punctuated by intermittent trauma spikes that occur at the stress point in each cycle. These cycles are facilitated by Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD) and, like the roles and their functions, are also fairly intractable. Four common cycles are defined and discussed allowing individuals to understand how these cycles are impacting them and offering them insight into methods they can use to slow the frequency and lessen the intensity of the resulting intermittent trauma spikes in an effort to find relief and improve quality of life (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 10: Consider Your Own Development

MacMillan's final step is reflective, encouraging individuals to consider their own personal development. MacMillan offers to complementary yet differing models of psychosocial development founded in Erik Erikson's stages of psychosocial development (1950, 1959, 1982). Her non-autistic spiral model and autistic staircase model draw on the findings of Diana Baumrind, Mihaly Csikszentimihalyi, and Jean Piaget.

Through understanding the impact of neurology on development and the differing ways autistics and non-autistics grow across the lifespan, all individuals, regardless of neurology, can work towards the psychosocial developmental milestones Erik Erikson offers and address psychological functioning differences (attachment, boundaries, identity, and intimacy (MacMillan, 2025).

By focusing on growth and self-improvement, individuals can contribute positively to their own development, their neurodiverse family dynamics and overall well-being and quality of life.

Conclusion

MacMillan's R.E.A.L. 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and improving one's own life and, whenever possible, one's neurodiverse family system. Professionals work with individuals rather than couples or family groups and emphasize that individual family members and neurodiverse family systems benefit when individuals focus on their own growth. Following these steps adds clarity and order to a situation that is often plagued by confusion, trauma and distress. The approach's educational elements support individuals in better understanding themselves and their neurodiverse family systems and its practical elements and quantitative assessments support action, decision making and positive life change.

MacMillan's 10-step approach not only addresses the challenges inherent in neurodiverse relationships but also empowers individuals to pursue the happiness and peace they deserve, regardless of neurology.

Resources for Further Exploration:

American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). DSM 5's Integrated Approach to Diagnosis and Classifications (pdf).

Brewer, R., Cook, R., & Bird, G. (2016). Alexithymia: A general deficit of interoception. The Royal Society Open Science, 3(10). doi:10.1098/rsos.150664

Broglia, E., Nisticò, V., Di Paolo, B., Faggioli, R., Bertani, A., Gambini, O., & Demartini, B. (2023). Traits of narcissistic vulnerability in adults with autism spectrum disorders without Intellectual disabilities" Autism Research. doi:10.1002/aur.3065

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Amazon link). Harper Perennial. (Republished in 2008).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (Amazon link). Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Applications of flow in human development and education (Amazon link). Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2015). The systems model of creativity (Amazon link). Springer.

Coolidge, F. L., & Segal, D. L. (1998). Evolution of personality disorder diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(5), 585-599. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00002-6

Crocq, M.-A. (2013). Milestones in the history of personality disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(2), 147-153. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.2/macrocq

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society (Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle (Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed.(Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company. (Republished in 1993, 1994, 1998).

Kinnaird, E., Stewart, C., & Tchanturia, K. (2020). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 55, 80-98. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004

MacMillan, A. (2025). Neurodiverse Family Systems: Theory and Practice. Available for pre-order.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism (pdf). Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 1.1-1.25. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244

Peterson, J. L., Earl, R. K., Fox, E. A., Ma, R., Haidar, G., Pepper, M., Berliner, L., Wallace, A. S., & Bernier, R. A. (2019). Trauma and autism spectrum disorder: Review, proposed treatment adaptations and future directions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 12, 529-547. doi:10.1007/s40653-019-00253-5

Reinhardt, K. M., Zerubavel, N., Young, A. S., Gallo, M., Ramakrishnan, N., Henry, A., & Zucker, N. L. (2020). A multi-method assessment of interoception among sexual assault survivors. Physiology and Behavior, 226, 113108. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113108

Rinaldi, C., Attanasio, M., Valenti, M., Mazza, M., & Keller, R. (2021). Autism spectrum disorder and personality disorders: Comorbidity and differential diagnosis". World Journal of Psychiatry, 11(12), 1366-1386. doi:10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1366

Skodol, A. E., Morey, L. C., Bender, D. S., & Oldham, J. M. (2015). The alternative DSM-5 model for personality disorders: A clinical application. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(7). doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101220

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Author of the R.E.A.L. 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach Available on the UnitusTI Cloud

About the Book

Neurodiverse Family Systems: Theory and Practice offers a groundbreaking framework for understanding the unique relational dynamics that emerge within families shaped by neurological difference. Bridging developmental theory, lived neurodivergent experience, and applied clinical insight, this book challenges conventional models and introduces a nuanced approach to working with autism, ADHD, and high body empathy across generations.

Essential reading for professionals seeking to deepen their understanding of neurodiverse relational systems, it invites a rethinking of how empathy, trauma, and identity operate within the family landscape—and how meaningful change begins with neurological clarity. connection, stability, and emotional peace.

© 2024 R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse

All Rights Reserved

anne@REALneurodiverse.com

Text or Call: (617) 996-7239 (United States)